And yet, like so many other dictators, not only was Amin a frightening, deeply disturbed man, but he was also effortlessly capable of ineffable charisma and charm. The president clearly enjoyed putting on a show.

By: Kimberly L. Bryant

“Movies are an authoritarian medium. They vulnerabilize [sic] you and then dominate you. Part of the magic of going to a movie is surrendering to it (…) The sitting in the dark, the looking up, (…) the people on the screen so much bigger than you: (…) Film’s overwhelming power isn’t news. But different kinds of movies use this power in different ways.” -D.F. Wallace

By all accounts, Idi Amin Dada is a rather interesting character. The operative word in that statement is, of course, character – oh, and feel free to exchange interesting for psychopathic.

As Ugandan’s president from 1971-1979, he is responsible for committing human rights violations by, literally, the hundreds of thousands. Notches on Amin’s rather large belt include, but are by no means limited to: the 1972 expulsion of all Asians from the country (leading to the country’s economic downfall); involvement in the 1976 hijacking of a French airline en route to Entebbe; the banishment of all Israelis from Uganda; the murder of countless intellectuals, Obote supporters, members of his own cabinet, ethnic groups such as the Acholi and Lango, and multitudes of others. Lest we forget to also mention the supportive telegram he sent to Hitler congratulating the great success of mass genocide.

And yet, like so many other dictators, not only was Amin a frightening, deeply disturbed man, but he was also effortlessly capable of ineffable charisma and charm. The president clearly enjoyed putting on a show.

These innate juxtaposed qualities of mass-murder and theatrical presence understandably makes Amin an attractive candidate upon which to base a script. Amin is at once a mystery when committing atrocities without remorse and an open book when he publicly spouts ludicrous views on leadership.

Amin the Character

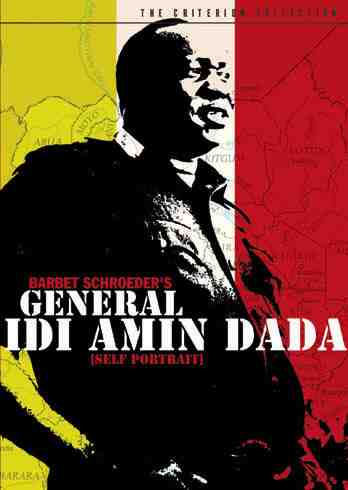

In fact, he was such an open book that he remains the only president in history to consent to having a feature-length independent documentary made about him. Directed by Iranian-born Frenchman Barbet Schroeder and released in 1976 for art-house film distributor Janus Films, General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait is the esteemed result of this audacious endeavour. Had Amin still been alive in 2006, he would have likely also been a supporter of Scottish director Kevin MacDonald’s commercial monstrosity, The Last King of Scotland. In addition to garnering numerous coveted awards, including two BAFTA’s and an Oscar for Forest Whitaker’s grandiose performance, the melodramatic film was quite lucrative and a seeming success. Though both films are based on the same larger-than-life man, their similarities end there.

“Commercial film doesn’t seem like it cares much about the audience’s instruction or enlightenment. Commercial film’s goal is to “entertain,” which usually means enabling various fantasies that allow the moviegoer to pretend he’s somebody else (…) and that life in general is just way more entertaining than a moviegoer’s life really is. (…) The fantasy-for-money transaction is a commercial movie’s basic point.” -D.F. Wallace

Made with a budget of approximately five million dollars for Fox Searchlight Pictures, The Last King of Scotland shows the infamous president as a charming monster, bordering on caricature – duly enhanced by Whitaker’s naturally lazy left eye. By focusing the majority of the plot on the misadventures of a white boy (James McAvoy) and the fallout of his foolish relations with one of the president’s many wives, The Last King of Scotland becomes about the consequences of Amin’s hideousness towards the young white character, rather than on Uganda. The Asian expulsion is mentioned in a few exposition-driven sentences during one of Amin’s press conferences in the film. These morsels inadequately represent the many atrocities that were committed during Amin’s rule. It downplays the reality, making it look like he’s murdered 3,000 people rather than 300,000.

An incredibly limited amount of screen time is devoted to showing these horrors. The few short clips of harrowing real footage from the original massacres are rudely flanked by long stretches of outlandish white-boy-drama. The impact of this authentic footage is all but lost amongst the rubble of ill-advised romantic escapades. For proof that this type of raw footage has the potential to be poignantly used, please see Ari Folman’s animated film Waltz with Bashir, a story based on consequences from the Lebanon War. Here, real footage of the massacres is shown to great effect at the end of the film. The sensitive material is buoyed by the film’s provocative, multi-faceted storytelling. Such is not the case with The Last King of Scotland, where the tragedy inherent in the real footage gets undermined, rather than upheld, by the surrounding storyline.

Is Accuracy Important?

With great power comes great responsibility. Appearing onscreen at the start of the film is the text, “This film is inspired by real people and real events.” A more accurate and less morally reprehensible preface to the film would have been, “This film is based on the novel of the same name.”

Based on the 1998 book of the same name by journalist-cum-novelist Giles Foden, the film is founded on fiction. Regarding historical accuracy, or lack thereof, Foden mentions in an interview, “Mainly I tried to hang onto to the idea that this was a story. I wanted to make people turn the page.” The popular and critically acclaimed book, which has received numerous literary awards, falls into the category of faction. The misrepresentation of history using the medium of literature has less wide-spread consequences than doing so using the medium of film: like photography, film holds an inherent sense of truthfulness – it is far easier to manipulate and persuade audiences using the medium of film than using the written word.

Fallout from this misleading representation is significant. When the film came out, Ugandans used it as a reference point for their own histories. “The reason for this film’s popularity is the disparity of historical knowledge that spans the generations. Seemingly not addressed for the youth by their education system, it appears that Ugandans are using this film to fill in their historical gaps, many referring to the ability for children to learn about their country (Capturing Idi Amin).” This reinforces the potentially omnipotent power behind the medium of film and how thoughtless representations can bring real-world consequences.

During one of the dramatic turning points in the film, Amin menacingly reveals to the main character – who desperately wants to flee the country – that he is in no way allowed to leave Uganda, declaring: “We are not a game Nicholas. We are real.” This particular period of Ugandan history, so filled with tragedy, is not a game to play for the sake of making a high-grossing film. The history and the people are very real and they deserve much better.

“Art film is essentially teleological; it tries in various ways to “wake the audience up” or render us more “conscious.” (…) An art film’s point is usually more intellectual or aesthetic, and you usually have to do some interpretive work to get it, so that when you pay to see an art film you’re actually paying to work (whereas the only work you have to do w/r/t most commercial films is whatever work you did to afford the price of the ticket).”-D.F. Wallace

On the other end of the spectrum, General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait (Général Idi Amin Dada: Autoportrait presents a subtly blatant and inquisitive independent documentary about a man who defies definition. Released in 1976, the film was shot in 1974 with Amin’s full consent, including the stipulation that he would be able to control what was filmed. Dir. Barbet Schroeder presents audiences with an even-tempered yet cutting reflection of the infamous president.

Though the film was literally made under Amin’s eyes, it manages to convey the dictator’s myriad atrocities and off-kilter demeanor far more effectively than did The Last King of Scotland. One way that General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait achieves this is through the use of observational voice-overs which unemotionally state various horrifying facts with juxtaposed footage, much of which was even specially set-up by Amin.

Renowned Spanish cinematographer Nestor Almendros poetically juxtaposes Uganda’s natural beauty with Amin’s voraciously bumbling and murderous character. Though Amin is obviously a psychopath – with crimes against humanity, siding with Hitler, feeding his staff to crocodiles, having his wife killed, dismembered, and sewn back together for his family’s viewing pleasure – he is entirely innocent in his own eyes. He sees himself as a hard-working fellow trying to do his best for the country. His astounding naiveté and lack of self-awareness are perhaps the film’s most surreal aspects.

Like The Last King of Scotland, General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait uses brief clips of real footage of Amin-instigated killings. Before the title credits even appear in the latter, the narrator lays out a succinct history of Uganda, including Amin’s activities and their subsequent effects on Uganda. This brief, informative montage of Ugandan life under Amin’s current leadership culminates with a clip of two young Ugandan women being executed. Tied to tree trunks, their bodies slump over after the rifles fire, fresh blood dripping down their legs. Cut to the title of the film onscreen, “General Idi Amin Dada: Auto-Portrait”. The point is made loud and clear.

Because of its placement at the start of the film, this tragic footage expresses the true horror of Amin’s widespread crimes and serves as a foundation upon which to view the rest of the film. Unlike the use of raw footage in The Last King of Scotland, here it is sufficiently anchored by the accompanying edifying voice-over and the film’s overall competent content.

The sum combination of audio and visual renders a clearly complex picture of a man whose vision of himself and the real-world reality of his actions are irrevocably out of synch. It also creates irony that provides humour throughout the film. A scene exemplary of this shows Amin floating down one of Uganda’s beautiful crocodile-filled rivers. The president is seen here as an unsophisticated, simple man gushing about his appreciation of the crocs. Hilarity subsequently ensues as it is widely known that Amin fed many a victim to these very crocodiles. One of Amin’s cabinet members even disappeared during filming, presumably meeting the same fate.

And yet, the peaceful beauty of the cinematography – the sunlit river, gentle colours, and limited camera movement – creates a serene backdrop upon which the scene plays out. This effectively mimics Amin’s seemingly peaceful mindset when committing these crimes.

Because Amin lacks the ability to critically think about the more ambiguous complexities in life, he sees multifaceted issues in purely black and white terms. For example, his motive to make Ugandan women hotel managers is because “the duty of the woman is a house woman – keep house.” Said proudly in broken English, he wears this statement as if it were a badge of progressive feminism. Further, his emotional immaturity crosses over into his responsibilities as the country’s leader. As he repeatedly states that the most important thing for a leader is to make the people of the country love you, he displays a child-like attitude toward love which lacks the necessary boundaries of a psychology healthy adult.

General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait is a simultaneously hilarious, yet serious; intimate, yet distant and overall calmly horrifying portrait of Amin. Raising questions based in factual truth, it works as a mirror to reflect not only the man behind the crimes, but asks what his existence says about us.

Cinematographic Truth

The Last King of Scotland fails because the only question it manages to raise is: who thought this was a credible use of 5 million dollars? By making The Last King of Scotland about a white boy’s hopeless choices and troubled romantic life, the film brings us further away from an already convoluted understanding of the truth. This film obscured Ugandan viewers by presenting itself as more truth than fiction and providing an unnecessarily inaccurate and unbalanced portrayal of an incredibly tragic time in the country’s history.

Conversely, General Idi Amin Dada: A Self-Portrait contains no viewer manipulation, no swelling soundtrack, no extraneous characters that take-away from the already densely disturbing plot. It demands the viewer work to understand, to question, to critically think about not only the man himself, but what his character might say about humanity in general. Now a part of the elite Criterion Collection, deservedly so, the restored version still leaves out the final poignant piece of text originally used to end the film:

“After a century of colonization, let us not forget that it is partially a deformed image of ourselves Idi Amin reflects back at us.”-J. Nesbit

Kimberly Bryant is a traveling writer, photographer and art critic.